Adaptive cruise control explained

In theory, traditional cruise control systems are flawless. Find yourself a long road, dial in a speed of your choosing, and, with precious little steering to worry about on Australia’s endlessly straight highways, you can simply sit back and relax.

Real life, unfortunately, is a little more complicated, and if you’ve ever rounded a blind turn with the cruise control set to 110km/h, only to find yourself charging into a herd of slow-moving, or stationary, cars, you’ll know the heart-pounding panic that comes with desperately searching for the brake pedal.

Likewise, when a car to your left attempts a Frogger-style lane change, despite travelling 30km/h slower than you, a cruise control system that’s got you locked to a particular speed goes from handy to hazardous in a hurry.

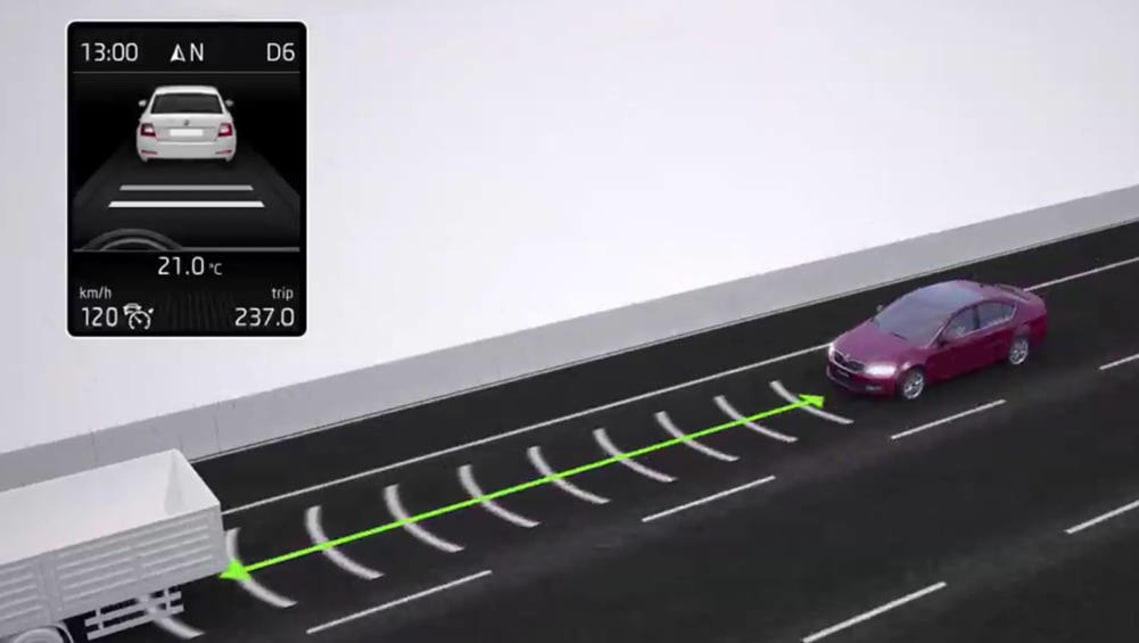

An adaptive cruise control system, also known as active cruise control, helps mitigate those risks by automatically adapting to changing traffic conditions, slowing down or speeding up with traffic as needed.

Way back in 1992 (the same year Australia’s one- and two-cent coins were withdrawn from circulation), Mitsubishi was putting the finishing touches on a world-first laser-based technology it dubbed its Distance Warning System.

The majority of systems are now radar-based, and constantly measure the road ahead for other cars.

While it was unable to control the throttle, brakes or steering, the system could identify vehicles ahead and alert the driver to begin braking. Rudimentary, sure, but it was the first baby step toward the adaptive cruise control systems used today.

By 1995, Mitsubishi had tweaked the system to begin slowing when it identified a car ahead, not by braking but by reducing the throttle and downshifting gears. But it was Mercedes who reached the next big breakthrough in 1999 when it introduced its radar-based Distronic cruise control. The German system could not only adjust the throttle to maintain a safe distance from the car in front, but could also apply the brakes if necessary.

The Distronic system was an auto-industry first, and was introduced on Mercedes’ traditional outlet for its newest technology: the then all-new (and circa-$200k) S-Class. So cutting edge was the system that even on its most expensive model, Distronic was an extra-cost option.

For the next decade, the technology was exclusive to the flagship models of premium marques, including BMW’s Active Cruise Control, added to the 7 Series in 2000, and the Audi Adaptive Cruise Control system, introduced on the A8 in 2002.

But where the luxury brands go, everyone soon follows, and cars with adaptive cruise control are available from just about every manufacturer in Australia. And the technology is more accessible than ever before. The Volkswagen Adaptive Cruise Control system, for example, has been shared across its vast range of cars, with the technology now standard on the entry-level Skoda Octavia, yours from $22,990 (MSRP).

So just how does this marvel of modern technology work? The majority of systems are now radar-based, and constantly measure the road ahead for other cars. The driver (that’s you) then dials in not just their desired speed, but how big a gap you want to leave between you and the car ahead, which is usually measured in seconds.

The program will then maintain that gap, regardless whether the car ahead slows down, gets stuck in traffic or, on the better systems, stops all together. When the traffic ahead speeds up, so will you – topping out at your pre-determined top speed. And if a car should pull into your lane unexpectedly, your car will automatically brake, maintaining the same gap between the new car in front.

The speeds at which the system works, along with exactly what situations it will respond to, varies depending on the manufacturer, so have a good read of your owner’s manual before you fully invest your trust in it.

It’s impressive technology, but it’s not without its drawbacks, the biggest of which being that if you’re not paying attention, you can find yourself stuck behind a slow-moving car for endless kilometres as the system automatically adjusts its speed to maintain its distance, before you finally notice and overtake.

But that’s probably a small price to pay for a system that can save you from the unexpected.

Comments